Chapters

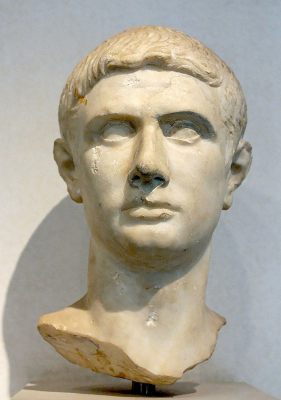

Marcus Iunius Brutus was born in 85 or 78 BCE. He was a politician, military commander, orator, and Roman writer. As an optimist, he was a supporter of the republic and an opponent of the dictatorships of Pompey and Caesar. He was friends with the orator Cicero. He was among the leaders of the plot against Caesar and was one of the dictator’s killers. In the European tradition, the name Brutus has become a symbol of a traitor and murderer fighting for a just cause. He was dubbed Tyrankiller.

Brutus’ birth date is disputed. The texts of Cicero show that Brutus was born in 85 BCE. Velleius Paterculus states that Brutus died at the age of 37, that is, he was born at 78. Both dates have their supporters among researchers.

Origin

He was the son of Marcus Junius Brutus the Elder, a people’s tribune from CE 83, and of Serwilia, half-sister of Marcus Porcjus Katon. After his father’s death (he died in strange circumstances by Pompey the Great), in 59 BCE he was adopted by his mother’s brother, Quintus Servilius Cepion, and officially took the name of Quintus Servilius Cepion Brutus (Quintus Servilius Caepio Brutus) but didn’t use it. He was carefully educated rhetorically and philosophically. He studied in Athens with the academic philosopher Aristos, brother of Antiochus of Ascalon. He was twice married – to Claudia, daughter of Appius Claudius Pulcher, and then Porcia, daughter of Marcus Porcjus Kato the Younger.

Some ancient authors report rumours that Brutus was the son of Gaius Julius Caesar. They resulted from the fact that Serwilla was Caesar’s long-time mistress. Researchers who set Brutus’ birthday to 85 BCE dismiss these rumors, since Caesar was 15 at the time. On the other hand, scholars who advocate Brutus’ birth in 78 BCE do not rule out such a possibility but consider it very unlikely.

Political career

Brutus highly respected his Uncle Cato. His career began as an assistant to Cato. In 58 BCE he took over the bursar of Marcus Porcius Cato, who received the governorship of Cyprus. There he got rich, mainly thanks to lending at interest. Some authors accused him of tax extortion and usury. Brutus was also active in Cilicia a year before Cicero became the proconsulate of the region. When he returned to Rome, he was already a rich man; he also married Claudia Pulchra.

Brutus was probably a senate in 57 BCE, but he continued to do profitable business in the eastern provinces of the empire. With his first speech, he proved his support for the optimists, thus opposing the triumvirs. When in 49 BCE there was Caesar’s civil war against Pompey Brutus sided with Pompey. He fought in the battles of Dyrrachium and Pharsalus. Before the battle of Pharsalus, Caesar admonished his officers to take Brutus prisoner if he voluntarily surrendered; but if he defends himself, please leave him alone and not hurt him. After Caesar’s victory, Brutus decided that the war was over and surrendered to Caesar in a letter. He asked him for forgiveness, which he immediately received.

For Caesar, the acquisition of Brutus, a representative of powerful Roman families and son-in-law of Cato, was politically advantageous. The intercession of Serwilla, the mother of Brutus and Caesar’s mistress, was also important. Therefore, Brutus, although he did not hide his republican convictions, found favour in the eyes of the dictator. Caesar entrusted Brutus in 46 BCE with the governorship of Gaul Cisalpina and in 44 appointed him praetor. Neither the defence against the dictator of the king of Galatia, Deiotarus, nor the open admiration for Marcus Marcellus, consul of 51 BCE, who after the battle of Pharsalus, in protest decided not to return to his homeland and live as an exile on Lesbos, did not hurt Brutus. This admiration was expressed by Brutus not only by demonstratively visiting the exile but by devoting to him the letter On Virtue. This work, dedicated to Cicero, strengthened the cordial knots that had long bound the two republicans.

In June 45 BCE Brutus divorced his wife and married Porcia, daughter of Cato the Younger. Cicero reported that there was a scandal related to the divorce – Brutus had no greater reason to part with his wife than just a desire to marry Porcia. The new marriage also made Serwilla’s mother hate Porcia.

Assassination of Caesar

Over time, many senators increasingly feared Caesar’s rule and his appointment as a life dictator (dictator perpetuo).

Brutus was a descendant of Lucius Junius Brutus, who drove out the last Roman king, Tarquinius. Hopes were therefore linked to the overthrow of the dictatorship. His heritage did not allow him to forget the inscriptions that appeared every night on the official chair where he sat as praetor – You are sleeping, Brutus or You are not Brutus. No wonder he was one of the leaders (along with Cassius) of a group of conspirators, ranging from sixty to eighty supporters of the republic that had planned the assassination of Caesar. The dictator ignored the warnings and on March 15, 44 BCE, he came to the senate, to the curia at the stone theatre built by Pompey. Unarmed, unprotected, died under the blows of several dozen daggers. Brutus was among the killers.

[ramka_ze_zdjeciem img="24884" imgw="600" alt="Assassination of Caesar, Vincenzo Camuccini" float="center"]Assassination of Caesar, Vincenzo Camuccini

After the murder of the “tyrant”, Brutus, raising the bloodied dagger upwards, mentioned Cicero’s name, congratulating him on regaining his freedom. He had no one to deliver the prepared speech to, as the senators left the curia in a panic. He was left with only a group of conspirators, and unable to pass a resolution to restore the republic, he led the assassins to the Capitol with his sword drawn. They walked – as Plutarch reported – not as if they were running away, but as if enjoying their deed, and full of pride they called the people to freedom, drawing into their ranks the most distinguished citizens encountered along the way.

From the Capitol, Brutus sent messengers to prominent representatives of the republican party with a summons to a conference which had a dramatic course. Brutus, against the majority’s advice, decided to keep Marcus Antony alive. He considered him a legal consul and decided to negotiate with him. At the Forum Romanum, a popular assembly was convened at which Brutus spoke. The speech, the content of which is known from Appian’s message, was received coolly, but no demonstrations against Brutus took place. The words about the murder of the tyrant and the restoration of republican freedoms did not captivate the crowds. The attack on Caesar’s parcel of land, as unjust and coupled with the grievances and laments of other citizens, was awkward to the colonists present in Rome who owed their plots to Caesar. Brutus’ assertion that the colonists could not feel safe having reached their estates unjustly was almost provocative.

Meanwhile, Antony called a session of the senate for March 17. The resolutions adopted on it were of a compromising nature. At the request of Cicero, an amnesty was passed, but Caesar has not declared a tyrant, and all the dictator’s orders were approved – including the right for veterans to own the land they had received from Caesar. Thus, Brutus became a criminal using amnesty, although the resolution was drafted in a way that did not offend his dignity.

On March 18, Antony received Brutus with a dinner, during which he stated that, as a consul, he could not guarantee the safety of the guest against the growing rebellion of the inhabitants of Rome. Brutus agreed to leave town. Since the law did not allow the incumbent praetor to leave the capital for more than ten days, Antony issued an edict allowing Brutus to stay outside the city for longer than allowed. Brutus left for the nearby Lanuvium.

War with Antony and Octavian

On June 5, in the Senate, Antony proposed that Brutus be entrusted with the function of supplying Rome with grain from Asia. In this way, he wanted to remove him from any significant influence on political life. This proposal touched Brutus, who saw it as a kind of political degradation. During the conference on June 8 in Antium, attended by Brutus, Cassius and Brutus’ mother and wife, Cicero advised him to take the grain function and go to Asia, which the rescue of the Republic depends on. Brutus, however, delayed his departure. In July, in the absence of Antony, he appeared in the senate and was nominated for the governorship of Crete. In response, in the first days of August, Antony issued an edict directed, inter alia, against Brutus, which did not lack threats and insults.

At the end of August 44, Brutus left Italy and gathered in Greece the remnants of Pompey’s army scattered after the Battle of Pharsalus. He accepted many young Romans studying in Athens on his staff, including the son of Cicero and the aspiring poet Quintus Horace Flakkus. At the head of this improvised army, Brutus threatened the Macedonian governor with war and took the province without resistance, and then dragged Roman troops in Illyria to his side. In January 43 BCE, after a short siege, he captured Apollonia.

In February, at the request of Cicero, he was officially nominated by the Senate as governor of Macedonia and Illyricum. For the victory over the Thracian tribe of the Bess, the army proclaimed him emperor, i.e. the commander-in-chief. As governor, he issued proconsular coins bearing an inscription referring to the attack on Caesar (Idibus Martiis) and an image of the so-called cap of freedom (worn by slaves during the liberation ceremony) between two naked daggers.

In the summer of 43, Brutus entered Asia and occupied this Roman province, joining forces with the forces led by Cassius from Syria. By the end of the year, Brutus and Cassius had captured all the eastern provinces and subjugated their rulers, dependent on Rome. In the spring of 42 BCE, Marcus Antony commanded twenty-five legions, Octavian eleven, and Lepidus seven. Against the triumvirs, Cassius had twelve legions under his command, and Brutus eight. The Brutus fleet ruled the Adriatic and the Aegean Sea.

Death

Antony decided in the summer of 42 BCE to wage war against Brutus solely on his own. However, Brutus’ fleet prevented him from crossing the Adriatic Sea. Antony called on Octavian for help, and the combined troops of the triumvirs broke the blockade and advanced deep into Macedonia. There, they were blocked by the armies of Brutus and Cassius, who fortified themselves in a difficult position at Philippi, while Brutus’ fleet in the Adriatic attacked Antony and Octavian’s supply convoys. Antony, however, built an earth rampart between the Republican camp and the port and forced Brutus and Cassius to fight.

In the first battle of Philippi on October 3, Antony crashed Cassius’ troops on the right flank. Believing that the Republicans had failed, Cassius committed suicide. However, on the left wing, the bold commander Brutus forced Octavian’s legions to retreat. The battle was undecided, both armies returned to their initial positions. Brutus took command of the entire republican army. Three weeks later, on October 23, Antony forced Brutus into battle again. The numerical superiority of the triumvir troops caused the defeat of the republican troops. Brutus, not wanting to be captured, committed suicide.

Marcus Antony showed Brutus respect. He had his body wrapped in an expensive purple cloak (he was later stolen and the captured thief was killed) and then cremated. The ashes were returned to his mother. Wife of Brutus – Porcia committed suicide upon the news of her husband’s death. According to Plutarch, however, she is not sure if it was her husband’s death that led her to this decision.

Literary and speech creation

There were known three philosophical writings by Brutus. Only short quotes from other authors have survived:

Brutus was also a historian; he made excerpts from the works of the annals of Fannius and Celius Antipater. Before the Battle of Pharsalus, he had been working late into the evening to summarize the work of Polybius. He also wrote poems. As Tacitus said: not better than Cicero, but happier because fewer people know about it. Pliny mentioned him among the authors who wrote erotic poetry. Historical works and Brutus’ poetry have been lost.

Brutus was friends with Cicero, who considered him a great orator. Cicero dedicated to Brutus Stoic paradoxes, On the highest good and evil, Tuskulanki and On the nature of gods. But he was an opponent of the impersonal and simple style used by Brutus. In a letter to Attica, he said: if you remember Demosthenes’ thunders, you will understand that you can speak as Attic as possible and at the same time in a sublime manner. Cicero. Cicero, in gratitude to his friend for dedicating to him the treatise On Virtue, titled his history of Roman pronunciation Brutus.

Only small fragments of Brutus’ speeches have survived. The speech he gave in the Capitol after the murder of Caesar was especially famous. Before its release, he sent it to Cicero with a request for correction. Cicero assessed it as a text full of great thoughts and words but added: if I were to speak on the subject, I would speak more hotly.

Brutus’ best speech was considered to be a speech in the Senate of 52 against the imposition of Pompey’s dictatorship. One sentence from this speech has survived: it is better not to order anyone than to serve someone; without the former one can live honestly, life with the latter is impossible at all.

In the same year, Brutus published Milo’s unspoken defence. Unlike Cicero, he tried to show that Milon had done well to his homeland by killing Clodius. Cicero did not like this way of argumentation, in his famous speech did not deny Milo’s guilt, but proved that the killer acted in self-defence. In 50 CE in Rome, Brutus defended his father-in-law Appius Claudius Pulcher, and in 47 CE king Deiotarus was against Caesar in Nicaea. In 43-42 he spoke in Greece, violently attacking Octavian. He also published two laudations – one in honour of his father-in-law, who died in Euboea in 48, and the other in honour of Cato, who committed suicide in Utica.